Every Easter morning, Christians around the world greet each other with the joyful words: “He is risen!” The response echoes with conviction—“He is risen indeed!”

These three words have traveled through centuries of faith, language, and worship. Yet, many ask: Why do we say “He is risen” instead of “He has risen”? Both phrases appear in Christian speech, Scripture, and music, but they carry different grammatical histories and theological undertones.

This article dives deep into the linguistic roots, biblical usage, and enduring power behind these two resurrection declarations. You’ll discover how grammar meets faith—and why both phrases still matter today.

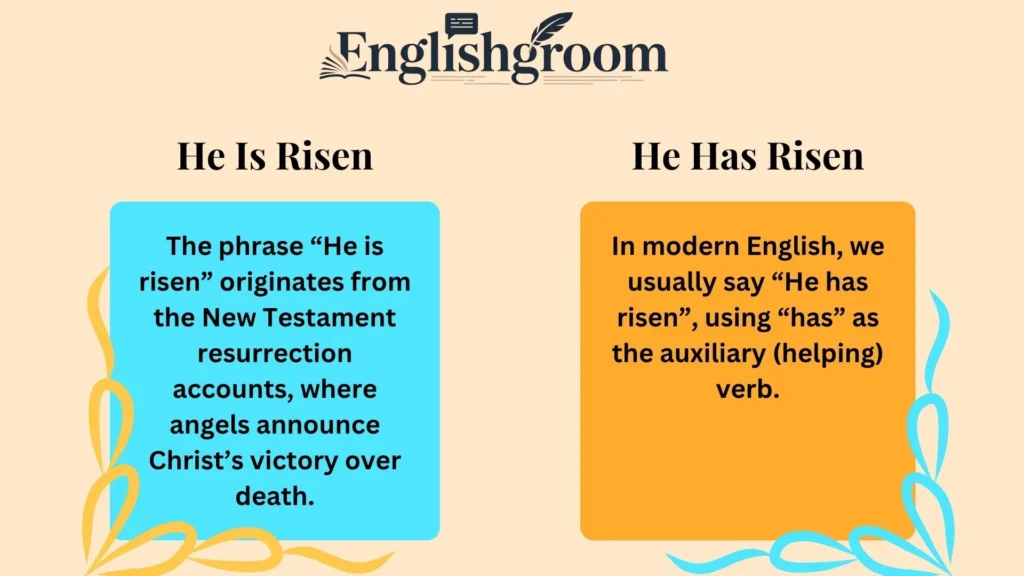

Understanding the Phrase “He Is Risen”

Definition and Origin

The phrase “He is risen” originates from the New Testament resurrection accounts, where angels announce Christ’s victory over death. For instance, in Matthew 28:6 (KJV), the angel declares:

“He is not here: for he is risen, as he said.”

This short sentence became one of the most celebrated affirmations in Christianity. It doesn’t just report an event—it proclaims a living truth.

In early Christian worship, “He is risen” functioned as a liturgical acclamation, meaning it was spoken publicly as a declaration of faith. Over time, it became the hallmark of Easter Sunday greetings in almost every Christian tradition.

Cultural Resonance

“He is risen” endures because it feels timeless, sacred, and rhythmic. Its structure mirrors ancient English phrasing, giving it a solemn tone that fits the holiness of the resurrection.

It appears in:

- Hymns and carols (e.g., “Christ the Lord Is Risen Today”)

- Easter sermons and liturgies

- Art and iconography from the early Church to today

Even non-religious people recognize the phrase as symbolic of renewal, hope, and triumph.

The Grammar Behind “He Is Risen”

Explaining the Archaic Form

In modern English, we usually say “He has risen”, using “has” as the auxiliary (helping) verb. However, older English used “be” instead of “have” for certain intransitive verbs—especially those involving movement or change of state.

Examples from Early Modern English:

| Verb | Archaic Form | Modern Form |

|---|---|---|

| go | He is gone | He has gone |

| come | He is come | He has come |

| rise | He is risen | He has risen |

So when translators of the King James Bible (1611) rendered Matthew 28:6 as “He is risen,” they were using correct grammar for their time. The “is” auxiliary highlighted a change of state—Christ has entered a new condition: from death to life.

Usage in Early Modern English

During the 15th to 17th centuries, “be” auxiliaries were common for verbs indicating transformation or movement:

- “The sun is set.”

- “The king is come to his throne.”

These forms slowly disappeared as English evolved, replaced by “have” in everyday usage. But religious phrases often preserve older grammar, much like fossils of language history.

How It Sounds Today

“He is risen” sounds poetic and elevated, even to modern ears. It belongs to the language of Scripture and worship, not casual conversation. Its archaism gives it a sense of timeless reverence, making it more powerful in liturgical and musical settings.

People continue to use it not because it’s grammatically modern, but because it feels eternal—anchored in history and holiness.

The Nuance of “He Has Risen”

Modern Grammatical Structure

“He has risen” follows modern English grammar rules, where “has” works as the auxiliary verb for perfect tenses. It belongs to the present perfect tense, which connects a past action with its current relevance.

Example:

- “He has risen” = He rose, and the effects remain true now.

So while it feels more contemporary, it still carries profound meaning: Christ rose in the past, and that truth still shapes the present.

The Meaning Shift

The change from “is” to “has” subtly shifts emphasis:

- “He is risen” focuses on the state—He is alive right now.

- “He has risen” emphasizes the action—the resurrection event has happened.

Both are true, but the former feels declarative, while the latter feels descriptive. That’s why most modern Bible translations favor “He has risen,” yet churches continue to say “He is risen” in worship.

Scriptural and Translation Evidence

Comparison Across Versions

Here’s how different Bible translations render Matthew 28:6:

| Translation | Phrase Used | Publication Year |

|---|---|---|

| King James Version (KJV) | He is risen | 1611 |

| New International Version (NIV) | He has risen | 1978 |

| English Standard Version (ESV) | He has risen | 2001 |

| New Living Translation (NLT) | He has risen | 1996 |

| Douay-Rheims | He is risen | 1582 |

Older versions mirror the Early Modern English structure, while newer translations align with current grammar.

Why Translators Differ

The Greek verb used in Matthew 28:6 is ἠγέρθη (ēgerthē), an aorist passive form meaning “has been raised” or “is risen.” This ambiguity allows translators to choose between “is” or “has” depending on theological nuance or linguistic style.

Older translators leaned toward liturgical beauty and continuity.

Modern translators prefer clarity and accessibility for contemporary readers.

Cross-Referencing Gospel Accounts

Across the four Gospels, resurrection announcements vary slightly:

- Matthew 28:6 (KJV): “He is risen.”

- Mark 16:6: “He is risen; he is not here.”

- Luke 24:6: “He is not here, but is risen.”

- John 20 focuses more on eyewitness accounts rather than direct angelic proclamation.

This consistency reinforces how deeply embedded the phrase “He is risen” is in Christian Scripture and tradition.

Theological and Doctrinal Implications

“He Is Risen”: Ongoing Truth

Theologically, “He is risen” declares more than an event—it affirms an ongoing reality. Christ is alive now, reigning eternally.

“If Christ has not been raised, our preaching is useless and so is your faith.” — 1 Corinthians 15:14

This form captures the perpetual presence of Christ in believers’ lives, emphasizing victory over death as an ongoing truth, not just a past act.

“He Has Risen”: Completed Work

“He has risen” points to the historical event—the moment in time when resurrection occurred. It fulfills prophecy and seals redemption’s completion.

It’s perfect for theological discussions that focus on the timeline of salvation history rather than ongoing experience.

Do Both Say the Same Thing?

Essentially, yes. Both proclaim the resurrection, but from slightly different perspectives:

| Phrase | Focus | Theological Emphasis |

|---|---|---|

| He is risen | State (He lives now) | Present reality of Christ’s life |

| He has risen | Action (He rose) | Completed work of resurrection |

Together, they form a fuller picture: Christ rose, and He still lives.

Language, Tradition, and Worship

Influence of Liturgical Traditions

Liturgical churches (Catholic, Orthodox, Anglican) have preserved “He is risen” in their Easter services for centuries. The call-and-response form—“He is risen!” / “He is risen indeed!”—anchors the Easter liturgy.

This repetition keeps the phrase alive, literally and spiritually.

Denominational Variations

Different denominations emphasize different expressions:

- Orthodox and Anglican traditions favor “He is risen.”

- Evangelical and Protestant circles often use “He has risen” in modern Bible readings.

Despite stylistic differences, all celebrate the same resurrection truth.

Linguistic Preservation in Religious Contexts

Sacred language tends to resist modernization. Religious communities often hold onto older forms because they connect worshippers to heritage and continuity.

Just as Catholics retain Latin phrases or Jews preserve Hebrew blessings, Christians continue to say “He is risen” as part of their identity.

Evolution of English and Religious Expression

From Old English to Modern Speech

Here’s a quick timeline of how auxiliary verbs evolved:

| Century | Common Auxiliary for “Rise” | Example |

|---|---|---|

| 12th–15th | is | “He is risen.” |

| 16th–17th | is/has (both used) | “He is come” / “He has risen.” |

| 18th–21st | has | “He has risen.” |

As English grammar standardized, “have” became dominant. But religious English often preserves archaic forms to evoke reverence and history.

How Language Reflects Theology

Language and theology often evolve together. Words don’t just describe belief—they shape it.

By saying “He is risen,” Christians affirm a living faith rooted in an eternal present tense. The phrase itself carries a rhythm of continuing victory, not just past triumph.

Contemporary Relevance

Even today, “He is risen” transcends language barriers. In every major Christian language, the phrase is recognized as a global Easter declaration:

| Language | Translation | Response |

|---|---|---|

| Greek | Χριστός ἀνέστη (Christos anesti) | Ἀληθῶς ἀνέστη (Alithos anesti) |

| Russian | Христос воскрес (Khristos voskres) | Воистину воскрес (Voistinu voskres) |

| Spanish | Cristo ha resucitado | En verdad ha resucitado |

| English | He is risen | He is risen indeed |

Cultural and Social Significance

Easter Greetings and Customs

Every Easter, Christians greet each other with “He is risen!”—a tradition dating back to early Christianity. It’s not just a saying; it’s a public proclamation of faith.

The exchange serves as a reminder of hope, marking the resurrection as the cornerstone of Christian belief.

Impact on Modern Media and Art

The phrase appears in:

- Literature: C.S. Lewis’s The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe reflects resurrection symbolism.

- Music: Handel’s Messiah and countless Easter hymns echo “He is risen.”

- Visual art: Depictions of the empty tomb often feature these words inscribed.

Even secular films and songs use “He is risen” imagery to represent rebirth and renewal.

Public vs. Personal Faith Expression

While churches proclaim “He is risen” publicly, individuals also use it personally to affirm spiritual renewal. It’s both communal and intimate—a bridge between history and heart.

Practical Guide: When to Use Each Phrase

| Context | Use “He Is Risen” | Use “He Has Risen” |

|---|---|---|

| Worship & Liturgy | ✅ Traditional, sacred use | ❌ Less common |

| Modern Writing/Teaching | ✅ When quoting Scripture | ✅ Grammatically current |

| Casual Conversation | ✅ Greeting form | ✅ Explanation form |

| Bible Studies | ✅ For discussing old translations | ✅ For explaining grammar |

| Easter Cards/Posts | ✅ Timeless and poetic | ✅ Modern and clear |

Both phrases work beautifully—it depends on tone, setting, and intent.

FAQs About “He Is Risen” and “He Has Risen”

What does “He is risen” mean in Christianity?

It means Jesus Christ has risen from the dead and remains alive today. It’s both a statement of fact and faith.

Why do older Bibles say “He is risen”?

Because Early Modern English used “is” as the auxiliary for intransitive verbs like “rise.” It was grammatically correct in 1611.

Is it wrong to say “He has risen”?

Not at all. It’s grammatically modern and theologically accurate. The difference is mainly stylistic and traditional.

Why do people still say “He is risen” today?

Because it carries spiritual weight and liturgical beauty. The phrase links today’s worshippers with centuries of Christian tradition.

Which should I use in writing or speaking?

Use “He is risen” for worship, poetry, or formal expressions. Use “He has risen” for modern discussions or teaching.

Conclusion

Whether you say “He is risen” or “He has risen,” both phrases declare the same eternal truth: Christ conquered death and lives forever.

“He is risen” connects you to history, echoing through the centuries of faith and language. “He has risen” brings that truth into today’s grammar, reminding us that the resurrection remains as relevant as ever.

So the next time you greet someone on Easter morning, remember—you’re not just repeating words. You’re declaring the heart of the Gospel.

He is risen. He is risen indeed.

Hi! I’m Sami, a 28-year-old content writer with a love for words and storytelling. Writing has always been my way of expressing ideas, sharing knowledge, and connecting with people. I enjoy creating engaging and well-researched content—whether it’s blogs, articles, or social media posts—that not only informs but also inspires readers. My goal is to turn complex ideas into clear, creative, and meaningful pieces of writing that leave a lasting impact.